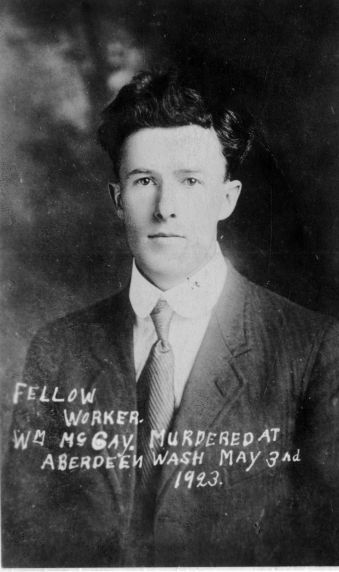

McKay was an activist and union supporter who was shot in the back of the head while on the picket line in Aberdeen, Washington on May 3, 1923

The Lumber Elite

Despite the widely held conception of lumbermen as freewheeling individuals, mill owners and boss loggers required little prodding to form their own associations to control prices, fight unions, and socialize with their own. Lumber and shingle mill owners like Robert Lytle and George Emerson rose to leadership positions in the regional and national lumber-trade associations. When the Hoquiam branch of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks formed in 1907, its membership consisted primarily of Hoquiam’s elites, including Frank Lamb, George Emerson, and Robert Lytle.

In 1912, during a strike of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) at several Grays Harbor and Pacific County mills, Hoquiam residents formed their own citizens’ committee, a hastily organized vigilante group composed of local businessmen, to physically remove the strikers from the embattled towns.

During the 1910s and 1920s, harbor lumbermen participated in a host of state-wide organizations designed to curb radical influences by hiring “detectives” who were essentially labor spies and by developing blacklists of militant workers. The U.S. Department of Justice and Department of War hired labor spies to keep watch over radical and union activities in Hoquiam, Aberdeen, and the surrounding woods during the late-1910s and 1920s. Washington State Governor Ernest Lister’s Secret Service, organized during World War I, also sent agents to cities in Grays Harbor to infiltrate unions, spy on radicals, and report on their findings to employers and local authorities.

William McKay, a logger and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was shot in the back of the head by a lumber company gunman. In appreciation for McKay’s years of service to the working class, the Industrial Worker ran a memorial reading, in part, that “He died, as he often expressed to the writer, ‘I would rather die fighting the master class than be killed slaving for them.’ May his fighting spirit animate others.”

The IWW and Grays Harbor

In Grays Harbor the Wobblies organized primarily among lumber workers, establishing their first local in Hoquiam in early 1907. The local IWW grew dramatically during the Aberdeen Free Speech Fight of November 1911 to January 1912, when IWWs joined Harbor socialists in their successful efforts to overturn a municipal law banning left-wing political speeches in Aberdeen’s downtown. Efforts by Wobblies to establish a stronghold on the Harbor triggered a six-month-long coordinated attack on the radicals by Grays Harbor employers and agents of the state. Employers formed citizens’ committees – members hailed from local chambers of commerce – in Aberdeen and Hoquiam to disrupt and remove the IWW presence on the Harbor. The vigilante groups arrested and jailed activists, used fire hoses to disperse their meetings, sought to “starve out” strikers by refusing them credit at local merchants, imposed exorbitant fines for minor criminal offenses, deported activists from town, violently assaulted them with clubs and firearms, and raided and closed their halls. The Hoquiam Citizens’ Committee armed itself with shotguns and clubs, and formed a cavalry to ride down the strikers.

The Harbor Wobblies’ free speech fight won them national attention. For two months, news from Grays Harbor ran across the front page of the Industrial Worker. By January 1912, local IWWs had more than one hundred free speech fighters prepared to violate the ordinance and go to jail and face other forms of punishment. Faced with this determined opposition, Aberdeen municipal officials compromised with the IWWs. The city council passed a new ordinance that allowed street speaking without a permit on most of Aberdeen’s major city streets.

Within a month of the repeal of the speaking ban, Grays Harbor workers had formed three Wobbly locals, which hosted nightly street meetings and weekly hall lectures. In the Spring of 1912, fresh from their free speech fight victory of the Wobblies struck alongside militant immigrant lumber mill laborers in a conflict that Bruce Rogers appropriately called “The War of Gray’s Harbor.” Between March and May of 1912, thousands mill hands and loggers from Grays Harbor, Willapa Harbor, and the Puget Sound joined the strike, eventually shutting down dozens of operations throughout Western Washington. Longshoremen, shingle weavers, sailors, and electrical workers all struck alongside the mill hands. The immediate cause of the conflict was the low wages paid at the Harbor’s mills. One spokesman for the workers declared: “I have seen children—sons and daughters of the working mill hands—come to the back yard of the hotel and pick old scraps of meat and bread from the garbage cans. It is a living wage that the mill hands want, and they will get it.”[8]

The strike mobilized a multi-ethnic community behind the cause of the mill workers. On March 23rd, two parades, each a “half mile long” and fronted by women and members of the Finish socialist band, converged at Electric Park on the border of Aberdeen and Hoquiam. Thousands of striking workers and supporters presented a united front against Harbor employers in what was shaping into a region-wide general strike. Near the crowd’s center, atop a “large box,” rose an illustrious lineup of “speakers in many different languages.” Workers listened to a long series of speeches, sang and played “revolutionary music,” and carried signs reading: “We Are Striking for Living Wages.” Within a week of the initial walkout, strikers were “coming into the I.W.W. at the rate of from 125 to 150 daily, in Aberdeen alone.”

In the face of this workers’ revolt, employers, police, and labor spies again resorted to mass arrests, deportations, and beatings. Banker William J. Patterson, the head of the Aberdeen Citizens’ Committee, described the group’s actions: “we organized that night a vigilante committee – a Citizens’ Committee, I think we called it – to put down the strike by intimidation and force. . . . [W]e got hundreds of heavy clubs of the weight and size of pick-handles, armed our vigilantes with them, and that night raided all the IWW headquarters, rounded up as many of them as we could find, and escorted them out of town.”[9] In Aberdeen, between November 1911 and May 1912, citizens’ committee members and police deported scores of IWWs from town; a group of 150 more only narrowly escaped being shipped out of town in a boxcar by the timely intervention of workers from the Northern Pacific railroad. One Wobbly editorialist wrote, “The lumber strike at Grays Harbor presents a scene that resembles a composite photograph of the atrocities at Lawrence, Mass., and the barbarities at San Diego, Cal.”[10]

One result of the strike was that it contributed to the trend of local leftists shifting ideologically from parliamentary socialism towards revolutionary syndicalism. Of the hundreds – if not thousands – of Grays Harbor workers who joined the IWW in 1912, many retained an informal affiliation with the Wobblies, one that they revived four years later when local workers again organized themselves into IWW branches.

The Wobblies were strongest in Grays Harbor between 1917 and 1923. In the cities, logging camps, and beach communities, they organized domestic workers, loggers, construction workers, clam diggers, mill hands, longshoremen, and sailors. As was often the case, the Harbor Wobblies gained their greatest following among the large Finnish-American population. Between 1917 and 1939, the names of several hundred Finnish Wobblies from the Grays Harbor region appeared annually in the pages of the Industrialisti, the Finnish-language newspaper of the IWW.

In the midst of World War I, the Wobblies led Pacific Northwest workers in what was the largest lumber strike in U.S. history up to that point. Seeking to force employers to grant the eight-hour day and improve working conditions, IWWs and other unionists struck and paralyzed the Pacific Northwest lumber industry. In Grays Harbor the Wobs shut down all but one firm: the notorious Grays Harbor Commercial Company at Cosmopolis, a mill referred to as “the Western penitentiary” by unionists.[11] In mid-September the Wobblies took their strike “back on the job,” the radicals’ term for returning to work but utilizing a variety of tactics – slowing down, feigning ignorance of work processes, closely following safety regulations – in order to minimize production. Striking “on the job” had many advantages for the Wobblies. With workers on the job, securing scabs was made more difficult, and it enabled the “strikers” to continue to be paid while taking direct action in pursuit of higher wages and improved work conditions.

The strikers won higher wages and shorter hours at mills and logging camps throughout Grays Harbor and the wider Pacific Northwest. Summing up the IWW’s successes, Wobbly James Rowan concluded: “The strike was over. The organized power of the lumber workers had won against one of the most powerful combinations of capital in the world. Two hours had been cut from the work day, wages had been raised, and conditions in the camps improved one hundred per cent. The lumber barons claimed they had granted the eight hour day ‘voluntarily,–for patriotic reasons.’ In reality they had granted nothing. All they had done was to give the eight-hour day their official recognition, after it had been taken by the direct action of the lumber workers themselves. There was nothing else they could do.”[12]

The hard-fought wartime gains made by the IWW came at a bitter price. Patriotic clubs, strikebreakers, and hoodlums attacked prominent IWW speakers, rank-and-file Wobblies, and the group’s halls and meetings. In his book The Centralia Conspiracy,Wobbly Ralph Chaplin related news that a band of 4Ls lynched an IWW near the Grays Harbor County seat of Montesano. Chaplin spent ample time on the Harbor conducting research for The Centralia Conspiracy, about the 1919 Armistice Day Tragedy in Centralia. When a group of vigilantes tried to disrupt Chaplin’s 1919 speech in Aberdeen and menace the IWW Hall, large numbers of Wobblies and their supporters turned out to defend Chaplin and the Hall. He recalled that in response to this threat, each Wobbly “was armed with a loaded baseball bat.” According to Chaplin, 2,000 Wobblies and sympathizers turned out to defend him from the vigilante mob. One of the armed Wobblies warned Chaplin that “there’s going to be hell-popping” and “we don’t want you in on it. You’re married and have a long sentence hanging over your head already.” All told, noted Chaplin, two thousand workers turned out to protect the Aberdeen Wobbly hall.[13]

Employers and police clearly understood the significance of the radicals’ halls. Aberdeen vigilantes raided or destroyed IWW halls in Aberdeen and Hoquiam on multiple occasions between 1911 and 1922. In April 1918, state agents and local vigilantes “swarmed” into the Aberdeen hall, tore the sheathings from the hall, stole and destroyed the furniture, fixtures, a typewriter and phonograph, as well as the suitcases, blankets, calked boots, and other goods left by workers in the hall, all of which the vigilantes used to build “a ‘Liberty Loan’ bonfire in the street.”[14]

While hall raids and beatings proved popular among anti-radicals, employers’ best tools for fighting against the Wobblies proved to be federal and state-level legislation, particularly the Washington State criminal syndicalism law. Passed in early 1919, the law essentially made membership in the IWW illegal. Dozens of IWWs were arrested in Grays Harbor between November 12, 1919, and April 5, 1920. The dubious honor of being the first criminal syndicalism victim on the Harbor fell to Charles Riddle, a “logger transient,” whose crimes of being “suspected of being an IWW” and blaming the “capitalist class” for the Centralia tragedy earned him time in the county lockup.[15] In an attempt to gain guilty verdicts, prosecutors brought in professional witness and former Wobbly A. E. Allen, who testified about his knowledge of IWW death threats against public officials, the destruction of property, and “slacking on the job . . . during war days.”

Criminal syndicalism prosecutions continued in Grays Harbor for the next four years: eleven in 1919, six the next year, fifteen in 1921, while in 1922, the last year of its enforcement in the county, twenty-three IWWs were arrested for violations of the statute. Criminal syndicalism arrests were so widespread that a November 1922 issue of the Grays Harbor Post could boast that: “There have been prosecutions and convictions of IWWs during practically every jury term in the past two years.”[16]

In spite of this intense persecution, organization in Grays Harbor continued in haste. From 1921-1923, Grays Harbor Wobblies joined fellow workers across the United States by increasing their public actions, organizing repeated displays of power designed to challenge obnoxious laws, liberate their imprisoned fellow workers, and win bread-and-butter gains on the job. One aspect of the local Wobblies’ early 1920s revival was the formation of the Foodstuffs Workers’ Industrial Union (FWIU) 460, a local comprised of women and men, and organized primarily by Finnish-American immigrant women in Aberdeen during 1923.[17] The Wobbly activist Jennie Sipo, a one-time criminal syndicalism prisoner, served as the union’s organizer and headed the list of the union’s charter members.

In 1922-1923, IWW membership around the nation climbed precipitously. In late-1922, Wobblies laid an ultimatum at President Warren G. Harding’s doorstep: Either release all class war prisoners held in federal and state penitentiaries or face a general strike. The threatened strike was set to begin on May 1, the International Workers’ Day. At this point, 20 IWWs still awaited their release in the Washington State Penitentiary. Another 49 were held at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

On April 25, 1923, the Industrial Worker ran a giant headline reading: “Strike One –Strike All!”[18] Workers throughout the nation had already begun to pour off the job. Grays Harbor was one of the centers of strike activity. At the start of May, loggers had shut down at least forty camps. One Wobbly wrote that there were “30 or 40 men in each mill, distributing hand bills and talking to the workers as they come off the job.”[19] All told, approximately 4,000-5,000 Grays Harbor mill workers, loggers, longshoremen, and clam diggers struck to free class war prisoners in late-April and early-May 1923.

Determined to spread the strike, workers marched to Aberdeen’s Bay City mill where they set up informational pickets outside the mill gates. One the picketers was IWW logger William McKay. When McKay and his fellow workers arrived at the gate, company gunman E.I. Green met them. According to one witness, Green “was standing a short distance away [from the pickets], loudly taunting the crowd of men with abuse and vile language, including in his remarks something to the effect that no one belongs to the Industrial Workers’ Union but foreigners who cannot speak English.”[20] Outraged at the taunt, McKay stepped forward shouting: “Do you mean that for me?” During the quarrel, Green pulled his revolver and McKay, seeing the weapon, attempted to flee. As McKay ran, Green shot McKay in the back of the head, killing him.[21]

Wobblies took to the streets to commemorate McKay’s life. More than 1,000 working people marched from the funeral parlors in downtown Aberdeen to the cemetery in a massive funeral parade. Wobs carried a giant banner reading: “Fellow Worker McKay: Murdered at Bay City Mill by a Co Gunman May 3rd 1923. A Victim of Capitalistic Greed. We Never Forget?” While the IWW demanded Green’s prosecution, no one was ever brought to justice for McKay’s murder.[22]

The funeral parade of William McKay was among the last large-scale demonstrations by the IWW in Grays Harbor. But 1923 did not mark an end to the Wobblies in Grays Harbor.