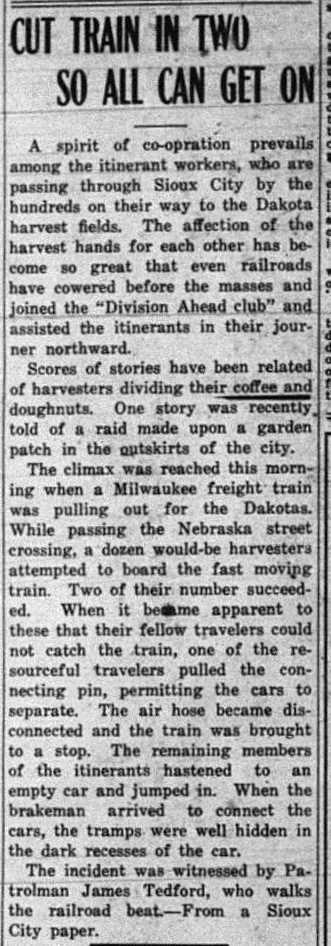

It was an overcast and windy day on September 1st, 1908 in Portland, Oregon when a gang of twenty men dressed in matching black overalls, white shirts, and red ties gathered in a train yard. These hoboes, led by J.H. Walsh, one of the hobo community’s premier labor activists, departed on a 2,500 mile journey across the country to the “hobo capital”. They jumped on to a cattle car and rode to Seattle, where they spent a night in jail for trespassing. After this they continued to hop freight trains to their destination. This group, self-labeled as the “Overall Brigade”, was busy along the way spreading the word about revolutionary industrial unionism to every encampment, boxcar, and hobo jungle they found. But they were not headed for Washington D.C., they were headed to Chicago, for the third annual convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was about to open.

This group of hobos were among those active in the fight for control over the union between those the Brigade dubbed the “homeguard”, a faction that wanted to use the ballot box as a path to socialism, and those who sought to reject electoral politics and labor contracts altogether. These men advocated for direct action, strikes, sabotage, and other forms of on-the-job protest as the surest way of dismantling capitalism. Those against the hobo contingent referred to them as “bummery”, theorizing that migrant and seasonal workers couldn’t be relied upon to be a revolutionary vanguard. The hoboes were ultimately successful in ousting the homeguard and dedicated the IWW to direct economic action exclusively.

This group of hobos were among those active in the fight for control over the union between those the Brigade dubbed the “homeguard”, a faction that wanted to use the ballot box as a path to socialism, and those who sought to reject electoral politics and labor contracts altogether. These men advocated for direct action, strikes, sabotage, and other forms of on-the-job protest as the surest way of dismantling capitalism. Those against the hobo contingent referred to them as “bummery”, theorizing that migrant and seasonal workers couldn’t be relied upon to be a revolutionary vanguard. The hoboes were ultimately successful in ousting the homeguard and dedicated the IWW to direct economic action exclusively.

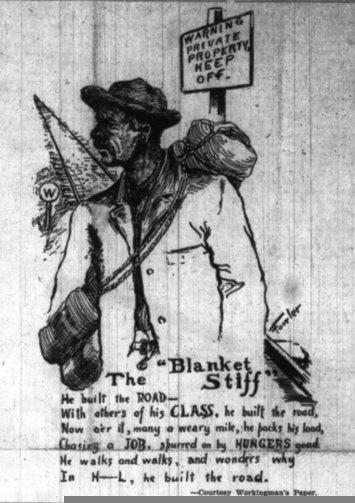

As they returned to the West they did so triumphantly, with a new and independent political movement of their own, one that promised the emancipation of all labor and the expansion of what constitutes a worker. Those concerned with the new changes were worried that the traits of the hobo lifestyle (things like job shirking, binge drinking, sexual promiscuity, and family desertion) were not conducive to leading an international movement aimed at social change. In true hobo style the men rejected any attempt to repudiate these attacks on their reputations, choosing instead to revel in their lifestyles, calling themselves “sons of rest” who preferred “simple life in the jungles” to the workaday world of the homeguard. This helped to create a folklore around the hobo that outlasted the original IWW movement and the subculture from which it emerged.

The Overalls Brigade lent itself to the creation of this folklore as it toured the West Coast. Before their trip to Chicago they had organized themselves into a red-uniformed Industrial Union Band, parodying popular gospel songs and hymns for street-corner crowds. They funded their trip through the sales of ten cent song sheets with four of their most popular numbers on it.

Upon returning from the trip Walsh realized how well they had sold and decided to make a full length book of these parody songs. Originally titled, Songs of the Workers, on the Road, in the Jungles, and in the Shops—Songs to Fan the Flames of Discontent, the volume went through numerous editions, eventually becoming known as the Little Red Songbook. This proved to be the most important cultural artifact of the hobos of the time. Along with the stories and commentaries of the road published in the IWW’s numerous newspapers and pamphlets, the Little Red Songbook provided hoboes with a powerful set of myths to enhance its group definition, vindicate its counter-cultural status, and mobilize its members for political action. The impact of this propaganda was swift and far-reaching. “Where a group of hoboes sit around a fire under a railroad bridge,” noted Carleton Parker in 1914, “many of them can sing I.W.W. songs without a book.”

This folklore helped them to solidify an identity to unify around. It also advanced the idea that hoboes were actually more revolutionary than their stationary counterparts. Unfortunately, this myth held the IWW back in organizing women, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and a whole host of immigrant groups from Europe and Asia. These identities were not seen as important as class, and this lead to the IWW relegating these groups to a supporting role in the hobo’s revolution. The IWW’s decades-long control over the hobo community and its myths delivered a certain subculture to the heart of American labor activism, but it also venerated the hobo as a manly white pioneer of the industrial West.

Organizing the Main Stem

The street in a town where hoboes tend to congregate is known as the “main stem”. This was the space that the Overall Brigade staked out as the headquarters for its revolution. These communities were drawn to these districts because of the anonymity and freedom from supervision. This also attracted Wobblies as a place to spread their message without worrying about employer interference. After returning from their trip Walsh began a campaign of soapboxing in order to recruit over a thousand members to Spokane’s IWW local, establishing an organizing model for others to follow. Tactics such as singing, street theater, jokes, parodies, and fiery sermons were soon adopted by Wobblies all over the West.

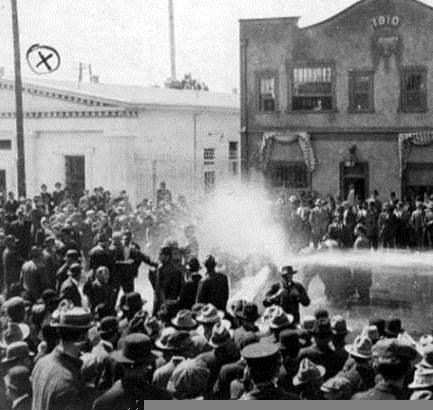

This bold claim to the main stem as a venue for public participation in revolutionary ideas was stiffly contested by local city officials. Walsh’s organizing was obviously very high-profile and this sparked heavy debate over the use of public urban space. Walsh also effectively used this organizing to boycott local employment agencies, causing the city to ban street-corner orations. In response, hundreds of Wobbly hoboes hitched rides to Spokane in order to defy the ban and serve their time in prison. The goal was to flood the jails with so many Wobblies that the city couldn’t arrest them all.

The City of Spokane bent to the demands of the protesters by March 1910, but similar “free speech fights”, as they were to be known, were breaking out all over the West. For the most part these campaigns were not aimed at protecting American civil liberties or the First Amendment. Instead, Wobblies fought for the collective autonomy of the hoboes and to challenge the stranglehold that the employers and the recruiting agencies played in the hobo job market. The process of city bans followed by an influx of Wobblies looking to get arrested was repeated over and over again, in San Diego, CA, Everett, WA, Fresno, CA, and even here in Aberdeen, WA.

But the actions of the Wobblies wasn’t just free speech fights with cities and marking out the main stem as their territory, they also focused heavily on delivering basic services to their members. Strategically located in the heart of the main stem, IWW halls offered kitchens, beds, reading rooms, employment information, and large meeting halls, where hoboes congregated on a nightly basis. Wobbly halls were seen more as places to curl up with a blanket and get a light, a stove, and companionship rather than a place to direct the union operations. In prohibition states, the IWW halls served as the only social substitute for the saloon.

By establishing themselves in the main stems of the West, these Wobblies were challenging city officials, the chamber of commerce, employment agencies, and crucially the popular commercial life of the main stem. The IWW actively strove to compete for the attention and money of hoboes with what they saw as “permanent dens of vice which smell to heaven, and which line the streets of the tenderloin quarter, and which need a thorough fumigation like that dealt out to Sodom and Gomorrah.” This according to the Industrial Worker, the IWW newspaper.

The IWW tried to respond to the perceived need for cultural uplift by putting on programming that attracted intellectuals and bohemians from bordering neighborhoods, interested in the cultural activity being put on by the IWW. Things such as films, concerts, plays, lectures, debates, and discussion groups found a ready home next to the all important radical bookstores that helped stimulate the intellectual life of the main stem. “In every large city there are hobo book stores which make a specialty of radical periodicals,” explained one migratory, “for even if the hobo does not generally belong to a socialistic society, he has been taught to think about class struggle. He may read the Hobo News, or he may read Jack London, or the Masses, or the Industrial Standard.”

These bookstores did far more than just sell books though. They served as replacements for the saloon, restaurant, and even in some cases lodging house. They also mostly all served as meeting spaces for radicals. Such cultural attraction often evolved into centers for labor organizing and radical agitation attracting all manner of intellectuals, artists, poets, and performers. But by far the most popular venues for raising voices of discontent were the public parks. Pershing Square in Los Angeles, Pioneer Square in Seattle, and Washington Square in Chicago were all important hobo resorts, especially during temperate spring and summer months. These hoboes spent their days listening to soapboxers in the parks across the West and Midwest. Most of the speakers were preaching about radical notions, but many proselytized from the Bible, trying to save the souls of the damned hoboes. Walsh and his Industrial union Band were formed to drown out these Christian preachers, and one of the main foes of the Wobblies on the main stem was the Salvation Army.

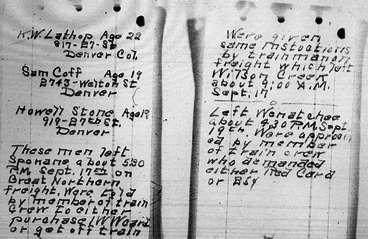

Alongside the spoken word the written word helped in spreading the ideas of the IWW on the streets of the West. Wobblies are famous for their many pamphlets and newspapers, the most important is undoubtedly the Industrial Worker published by the Spokane local. The newspaper featured local lodging houses, coffee shops, and second hand clothing stores, field guides for hoboes with prominent roads, jungles, and worksites, and tips on local judges, residents, train crews, and police forces around the West. Virtually every issue also featured “slave market news” that reported not only on the amount of hiring being done on a given main stem, but also on the hours, wages, job conditions, and fees that migratories could expect to find there. In doing so they wrested control over the supply of labor at the work camps, thus laying the groundwork for future direct action in the field.

It was not until 1913 that workplace activism began to show its face in the worksites of the West. The fieldwork began in California when “camp delegates” departed the main stems of Redding, Sacramento, Fresno, Bakersfield, Los Angeles, and San Francisco to recruit seasonal laborers on the job. Delegates swept through the orchards, harvest fields, and forests of the Central Valley and Sierra Nevada spreading propaganda and attempting to organize the floating army of “wage slaves.”

Bolstering these efforts was the notorious Wheatland hop pickers strike at E. B. Durst’s ranch near Marysville, California, in August 1913. This strike, led by several Wobbly hoboes who spoke for the multinational workforce of twenty-eight hundred, ended in a shoot-out that left four men dead, including a district attorney, a deputy sheriff, and two workers. In the wake of Wheatland, and the sentencing to life imprisonment of two Wobblies charged with murder, forty new IWW locals opened and one hundred soapboxers marched up and down the state signing up thousands of new members. Wobblies were notorious for disrupting normal labor camp routines, finding any excuse to agitate fellow workers on the job. “They stand on a nail keg and organize a strike,” remarked one employer, “and inside of a day one of them hits camp, hell’s a-poppin’.”

Despite this apparent victory, real on-the-job power being in the hands of hoboes was still a very long way off. In the Midwest Wobblies began to focus on delivering these material gains to workers. In April 1915 IWW delegates at special conference of harvest district locals voted to form the Agricultural Workers’ Organization (AWO), which soon became headquartered in an old cheap hotel building in Minneapolis’s Gateway district. The AWO used the tactics from California of mobile delegates traveling from town to town to organize harvesters, but this time focused on concrete issues of wages, hours, and working conditions. This lead to a sharp increase in the number of new members being signed up, with hundreds per week in 1915, a rate that would be topped in 1916 and 1917. The AWO was successful at transforming the whole industry of harvest migration, not only securing gains on the job but also ridding the jungles and boxcars of gamblers, stick-up artists, and extortionist railroad police. As they swelled to 70,000 members by 1917 the AWO expanded its operations into the lumber and mining industries of Montana, Idaho, and the Pacific Northwest.

The IWW had infused hobo subculture with political zeal. “To-day if you will get into a box car and meet a crowd of hoboes,” Ben Reitman wrote sometime after 1915, “you will almost imagine that you are in the Socialist or I.W.W. meeting.” Because of the IWW, he added, “the hobo has evolved from a despised shiftless creature to a powerful useful man.”

End of An Era

This dramatic rise in popularity of the IWW and its radical messages prompted an equally dramatic reaction from the local employers and law enforcement officials. As the United States entered the first World War in 1917, a war the Wobblies heavily denounced. This opposition to the war gave employers and their law enforcement agents the cover they needed to launch a massive counteroffensive against the union, accusing Wobblies of being traitors and even spies. Wobblies were also attacked by various vigilante groups allied with local police on numerous occasions because of their prominent role in many strikes that curtailed wartime lumber and copper production. These attacks laid the groundwork needed for the so called “Big Pinch” of September 5, 1917, when US Justice Department agents simultaneously raided IWW headquarters, halls, and private homes around the country. The agents seized virtually all the union’s records and property and arrested one hundred members under federal espionage laws. This was followed by prosecutions under newly passed state and federal sedition and criminal syndicate statues which saw leading Wobblies sent ot jail or hiding underground. The infamous Palmer Raids of 1919 and the virulent Red Scare that followed further inhibited Wobbly activities. By 1920 this once premier hobo organization stood on the verge of collapse.

In another sense, however, the crackdown against dissenters in general and the IWW in particular marked the beginning of a longstanding effort to resettle white men back into steady jobs and stable homes. This attempt at “welfare capitalism” in the 1920s did not entirely succeed, but it did provide a blueprint for later efforts. The main stem was in decline as early as 1919. Employment agencies were shutting down, and large-scale workingmen’s hotels no longer found financing. The population aged, and for the first time people began referring to the main stem as “skid row.” Folklorists even began to collect the songs, stories, and jargon of hoboes, who, as one folklorist put it, were “anachronisms bound for extinction.”

Yet it must be said that in its day the IWW was the most advanced working-class organization the United States had yet produced. The IWW wrote one of the most inspiring and brilliant chapters of the workers movement in the United States. A forerunner of events to come, the legacy of the IWW contains much that is imperative for the contemporary labor movement to relearn, with its rejection of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment, its emphasis on building power on the shop floor through the mobilization of the rank and file, and its radical appeal to the urgency and necessity of solidarity. An 1914 article published in the IWW’s publication Solidarity declared,

The nomadic worker of the West embodies the very spirit of the IWW. His cheerful cynicism, his frank and outspoken contempt for most of the conventions of bourgeois society. . .make him an admirable exemplar of the iconoclastic doctrines of revolutionary unionism. His anamolous (sic) position, half industrial slave, half vagabond adventurer leaves him infinitely less servile than his fellow worker in the East. Unlike the factory slave of the Atlantic seaboard and the central states he is most emphatically not “afraid of his job.” No wife and family encumber him. The worker of the East, oppressed by the fear of want for wife and babies, dare not venture much.

Sources:

Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America by Todd DePastino, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2003 by The University of Chicago.

https://isreview.org/issue/86/legacy-iww/index.html

https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/143783in.html

https://depts.washington.edu/iww/wobbly_trains.shtml#_edn1

J.H. Walsh, “IWW ‘Red Special’ Overalls Brigade,” Industrial Union Bulletin,September 19, 1908, 1.

David Arthur Walters, “The 1908 Red Special Campaign,” AuthorsDen.com, July 26, 2005.

J.H. Walsh, “IWW ‘Red Special’ Overalls Brigade.”

J.H. Walsh, “IWW ‘Red Special’ Overall Brigade,” Industrial Union Bulletin,September 19, 1908, 1.

J.H. Walsh, “Abroad in the Nation,” Industrial Union Bulletin, October 24, 1908, 1-3.

“IWW Newspapers,” Mapping American Social Movements Through the 20th Century.

Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the IWW (New York: Quadrangle, 1969), 86-87.

No title. Solidarity, November 21, 1914, 2-3.

Paul F. Brissenden, The IWW: A Study of American Syndicalism (New York: Russell & Russell Inc., 1920), 262.

Oliver Janders, “IWW Yearbook: 1909,” The IWW History Project, http://depts.washington.edu/iww/yearbook1909.shtml#_edn23

Greg Hall, Harvest Wobblies (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2001), 61.

Janders, “IWW Yearbook: 1909.”

“Another Free Speech Fight Go to Fresno,” Industrial Worker, September 3, 1910, 1.

“On the Road to Fresno,” Industrial Worker, April 6, 1911, 4.

Dubofsky, We Shall Be All, 190.

Roger N. Baldwin, “Free Speech Fights of the IWW,” Twenty-Five Years of Industrial Unionism (The Industrial Workers of the World: 1930), n.p.

“Fifth IWW Convention.” Solidarity, June 11, 1910, 3.

Charles Ashleigh, “The Floater,” International Socialist Review 15, (1914): 37.

Richard Reese, “The A.W.O. – An Example of a Successful Union,” Solidarity, March 18, 1916.

Frank Tobias Higbie, Indispensable Outcasts (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 153.

“Harvest Hands Must Protect Themselves,” Solidarity, October 09, 1915, 1.

“Did ‘Brakies’ Hold Them Up? No, They Were IWW’s,” Solidarity, December 25, 1914, 4.

Harry Howard, “A Sample of ‘Justice’ for IWW Members,” Solidarity, January 13, 1917, 3.

Greg Hall, Harvest Wobblies: The Industrial Workers of the World and Agricultural Laborers in the American West, 1905-1930 (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2001, 4.