Social Movement or Cult?

In his book, The Politics of Permaculture, Terry Leahy describes permaculture as being guided by the charismatic authorities who initially developed the design system. Leahy adopts the definition of the term ‘charismatic authorities’ such that the authority is “tied to an individual personality who is considered extraordinary.” They are regarded as authorities because what they say and write is considered to be true by the followers, frequently being unchallenged or critiqued. It is this following that makes them charismatic.

Bill Mollison is probably the most well known name in permaculture, being the co-founder and developer of the system. He left school at 15 to help run the family bakery in Australia. Over the following ten years he worked many jobs that took him into natural settings such as shark fisherman, forester, and naturalist.

In 1956, at the age of 26, he joined and worked for the ‘Wildlife Survey Section’ of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Throughout the 1960s he worked as a curator at the Tasmanian Museum. His work with the Inland Fisheries Commission allowed him to resume his work in the field. In 1966, he entered the University of Tasmania. After he received his degree in bio-geography, he stayed on to lecture and teach, and developed the unit of Environmental Psychology. He retired from teaching in 1979.

His work with CSIRO is what inspired his lifelong passion with the permaculture he was developing. According to his student Toby Hemenway the original idea came to Mollison in 1959 while he was observing marsupials browsing in the Tasmanian rain forest, because he was “inspired and awed by the life-giving abundance and rich interconnectedness of this eco-system.

It was in the 1960s that he combined his personal observations with the study of multiple cultures around the world that he synthesized the concepts that would become permaculture. In the late 1970s he and David Holmgren “jointly evolved a framework for a sustainable agricultural system based on a multi-crop of perennial trees, shrubs, herbs (vegetables and weeds), fungi, and root systems” for which they coined the word “permaculture”. Holmgren was a student at the radical Environmental Design School in the Tasmanian College of Environmental Education. Mollison was a senior tutor in the Psychology Dept of the University of Tasmania.”

“After many years as a scientist with the CSIRO Wildlife Survey Section and with the Tasmanian Inland Fisheries Department, I began to protest against the political and industrial systems I saw were killing us and the world around us. But I soon decided that it was no good persisting with opposition that in the end achieved nothing. I withdrew from society for two years; I did not want to oppose anything ever again and waste time. I wanted to come back only with something very positive, something that would allow us all to exist without the wholesale collapse of biological systems.”

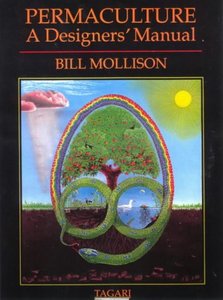

Mollison’s rise to the position of charismatic authority was a result of his writings on the subject,as well as personal appearances. His 1988 book Permaculture — A Designers’ Manual, is considered by most to be the definitive work and is the preferred text used by permaculture design courses. David became a charismatic authority after setting up his homestead Melliodora and publishing his reinterpretation of the design principles in his 2002 book, Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability.

Mollison’s rise to the position of charismatic authority was a result of his writings on the subject,as well as personal appearances. His 1988 book Permaculture — A Designers’ Manual, is considered by most to be the definitive work and is the preferred text used by permaculture design courses. David became a charismatic authority after setting up his homestead Melliodora and publishing his reinterpretation of the design principles in his 2002 book, Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability.

The writings of these two are the foundational texts of the permaculture movement, they define and explain what constitutes permaculture. “It is hard to imagine that any other author, now or in the future, could write a canonical work in permaculture. Even books which are widely influential in the movement, for example, Rosemary Morrow’s Earth Users’ Guide to Permaculture, are seen as commentaries, rather than as a part of the permaculture canon in their own right”, asserts Terry. This makes these texts what sociologist Dorothy E. Smith calls “canonical texts”. She says that discourse around canonical texts can create bonds within social movements.

One can find examples throughout history of the phenomenon of discussions around canonical texts building social movements. For example Karl Marx’s text sparked a revolutionary political movement that reshaped the world. Tim Berners-Lee at CERN in 1989 wrote the Hypertext Markup Language that would become the World Wide Web.

“…the definition of permaculture, the charismatic foundationalism that goes with a movement based on a canon of inspirational writings… these are problems that are not easy to address without calling into question fundamental structures that make our movement cohere.

I am concerned that young people who might in the past have embraced permaculture are now more likely to join the dots to combine agroecology and degrowth to arrive at a position similar enough to permaculture without being caught up in ‘permaculture’ as a named combination.”

This charismatic leadership is more akin to a cult than to a social movement, according to Leahy. But he claims that it is not a cult because the charismatic authorities have no ability to compel participation or bestow membership. The most common way someone is initiated is the PDC, or permaculture design course. This refers to the ability for all permaculture teachers to trace the lineage of their own education back to very initiators of the design system, those very first PDCs given by Mollison and Holmgren. According to Leahy this is another trait of the movement that resembles a cult. This method of authorization to practice permaculture is decentralized, with no legal requirements to become a designer.

“It could be said that while many may be ‘participants’ in permaculture as a social movement, the only true ‘members’ of the movement are those with a PDC (Permaculture Design Course)… the teaching of the PDC informs the permaculture movement and possession of the PDC confers incontrovertible ‘membership’”.

Despite these similarities there are distinct differences between permaculture and a cult. For example, a cult will typically attempt “social closure”, where members build all their social relationships around other members. Sociologists define cults as formations with a centralized organizational structure, rigid rules for membership and a top-down power hierarchy.

On the other hand participants of social movements continue to interact with the outside world. Social movements are held together through shared beliefs, even if those beliefs are interpreted differently by different participants. Unlike cults, social movements such as permaculture have leaders that contribute to the collective identity of the movement as a whole by influence instead of command.

Leahy related a story of a run in with some Spanish anarchists who had some critiques of the permaculture community they were visiting. These anarchist commented on the lack of radical actions happening in the community. With so many Indigenous rights issues going on in their backyards, these permaculturists had busied themselves building a nice lifestyle for them and their families, which served to close them off to the struggles happening around them. They had concluded that there is no radical permaculture challenging structural social injustices in Australia.

The use of the term eco-fascist began in academic circles to refer to a type of government which would place environmental measures above the needs and freedoms of it’s citizens. It has since been used by the mainstream to refer to individuals or groups who self-identify as eco-fascists. Eco-fascists combine far right talking points with environmentalism and advocate the Malthusian concept that overpopulation is the reason for the changing climate, the solution usually being genocide.

Environmental historian Micheal Zimmerman defined eco-fascism as “a totalitarian government that requires individuals to sacrifice their interests to the well-being of the ‘land’, understood as the splendid web of life, or the organic whole of nature, including peoples and their states”. He related this ideology to the organicist ideas Nazis had about “Blood and Soil”.

Colonization in Permaculture’s roots

In his book, The Politics of Permaculture, Terry Leahy argued that Mollison and Holmgren didn’t so much invent permaculture, as it is truly a collection of indigenous farming techniques repackaged for a modern audience, but that they invented the term to describe already existing methods of cultivation. As for these methods, they never attribute them to their original sources in their books but do mention that their good fortune in having a variety of useful plants and animal species first domesticated by people from a “variety of cultures”.

From the book,

“We do not hear that composting was a technology invented in ancient China, brought to Europe by Albert Howard and Franklin King, and popularized by Jerome Rodale, one of the originators of ‘organic agriculture’ in the West. We do not learn that growing maize with velvet beans was a technology pioneered by the Kekchi Indigenous people of Guatemala and Honduras and later taken up by scientific agriculture.”

The book is a sociological study of the community of permaculturists Leahy interviewed over the course of several months. Many raised the issues of wealth inequity and race. One lady, Niama was uncomfortable with the very idea of permaculture being invented by two white cis men, the very idea seemed colonialist to her. She compared it to the idea of Captain Cook “discovering” Australia. The book pointed to three reasons permaculture needed to be decolonized:

1. The failure to acknowledge Indigenous knowledge as the basis of permaculture.

2. The domination of the movement by white people. The failure to be inclusive.

3. Settler ownership and Indigenous land.

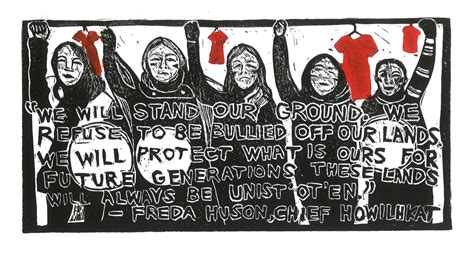

Some participants in the permaculture movement do own land, and when that land is stolen from indigenous cultures, that makes them settlers. In Permaculture Design Magazine, the ‘Decolonizing Permaculture’ issue includes this analysis by Jesse Watson, “Decolonization is about correcting past crimes committed by (mostly) European settlers by returning stolen land. Ideally, this process should be done without strings attached. Questions of what happens to present settler peoples is secondary to the act of returning Native land to Native peoples.”

But this approach on an individual level is akin to the calls for reusable straws and shopping bags, these gestures do nothing to address the root cause while actively harming working class farmers. Currently the wealthy own an enormous amount of the farmable land on this planet, and that will not be changed by poor white people giving over their small acreages to poor BIPOC farmers. What is needed is a revolution of the global food system that places demands for Landback front and center. This means giving the land back…at scale, on the level that could actually affect the global economy. This will not be accomplished by apolitical fence sitting. We will need direct action to seize the means of production for the common ownership.

Leftist tendencies in Permaculture

On the state level permaculture challenges systems. For this reason it is argued that it would not be permitted within the more authoritarian nations. Many see the system that permaculture challenges as industrialism, instead of capitalism and the State. Although the alternative is less well thought out than the alternatives offered by the anarchists.

Leahy says,

“The permaculturists I spoke with were divided on strategy to achieve system change. Quite a few praised permaculture as a ‘positive’ approach, a contrast to confrontational left politics. Others indicated that permaculture is moving away from an exclusively anti-political strategy. Some stressed the necessity for permaculture to influence regional and national policy. Some interviewees were participating in political lobby groups and supporting particular political parties. A common sentiment was the necessity to work on alliances with other groups.”

These are sentiments also expressed by the new leftists, who march forward with militant joy and plenty of solutions, where their ancestors were lambasted for providing nothing but critique. Perhaps there can be some common ground reached between the political left and the permaculture community on this frontier. As Leahy observes permaculture has a long track record of taking the advantages of the current system and using them to promote “hybrids of the gift economy and capitalism”. If we can dissuade permaculturists of this notion that capitalism can be saved then we can focus on real solutions.

Another complication is the fact that many people don’t want the homesteading lifestyle that permaculture has popularized. It remains the domain of the lucky few able to purchase the needed land and equipment to run such a farm. Very few professional permaculturists actually make their full time living from this teaching or designing work. Even worse is the trend of unpaid labor in the form of volunteers or interns, this practice is abused by some to take advantage of cheap or free labor without challenging the systems that make it impossible for a small farm to pay it’s employees a livable wage.

The strategy thus far for permaculture has been to leverage the discretionary income of the middle class to obtain land and begin to drive change towards a more sustainable society. This emphasizes doing what you can in your own life, through consumer and lifestyle choices, to bring about the sort of economic drivers for sustainable agricultural practices employed by permaculturists.

BIPOC and other marginalized minorities are typically poorer than their whiter counterparts in industrialized nations. Many of the same dynamics that exclude BIPOC individuals are the same that exclude the white working class. This is an opportunity for class solidarity that anarchist should seize upon and use in our organizing efforts in these spaces. We must stand with our BIPOC brothers and sisters and demand that more is done to end the current system than slow progressive reform.

We can’t rely on the purchasing of private land to bring about the type of environmental changes we want to see. We must open unused properties for community spaces, shelter, kitchens, and gardens; whatever is needed. These spaces allow those without access to resources to engage in community building by tapping into the shared resources of a community built on care. We need to be asking what each community needs and conducting listening sessions so that we know we are working towards meeting their needs, not fulfilling our own agendas. For settlers, learning from Indigenous people what can be done to develop their food autonomy and contributing financial resources to those ends is imperative. Give out whatever your product is, whether design or education, free of charge directly to BIPOC individuals. Permaculture needs to be politicized, and it needs to be prepared to be promblematized as well. There are many things we have examined to be wary of. The community needs to ally itself with and learn from already political organizations, especially BIPOC political movements.

Far Right Incursion

There has been a lot said about the association between the far right and new-age ideas such as spiritual thinking, self-help, health, and well-being trends. Carl Cederström, author of Desperately Seeking Self-Improvement: A Year Inside the Optimization Movement was quoted in a recent Guardian article saying, ‘Wellness has very strong ties to the self-help movement … and what you find at the core of these movements is the idea that you should be able to help yourself.’ Researchers and advocates have noted the rise in these same thought patterns underlying some responses of those in sustainability movement to the pandemic.

Leahy observed any ritual activity that a social movement engages in eventually becomes ‘codified, through which a vision of the world is communicated, a basic historical experience is reproduced’. These activities also serve to reinforce the collective identity and feeling of belonging among participants. The codification of this behavior is being demonstrated by the convergence between the far right and the more traditionally left leaning environmental movement spaces. Among the players at these anti-lockdown/anti-vaccine events are a small but vocal sub-group with more extremist and often fascistic motivations.

As Guardian journalist Myke Marlett noted in his piece,

“This is a form of fundamentalism where what you believe isn’t as important as what you don’t believe in. Whatever is happening, isn’t happening. Whatever reality is, they’re opposed to it. Which, I suspect, makes the movement uniquely dangerous.

So we can see that the ethics of permaculture are not immune to the corrupting influence of the far right. But this is not a new trend, it has historical roots in Nazi beliefs about the body, astrology, pagan festivals, organic farming, ecological education, and nature worship, as argued by journalist George Monbiot. Historian Andrea Gaynor also writes about similar far right influences in the early English organic movement. She has documented links between these early movements and Nazi ideology about immutable “natural laws” going back as far as 1946. Her work also found that these movements also proved to be a ‘happy hunting ground’ for recruits to more conservative organizations.

Alongside this historical connection, we have witnessed a recent rise in the far right mixing environmental ideas into their rhetoric. Eco-fascist have incorporated a doctrine of racialized permaculture into their thinking that reinterprets the ethics of permaculture in favor of a single race instead of applying it universally. The reason for all of this is the misguided notion that something like permaculture could be apolitical, when it concerns such political topics as how we design our life systems, where we get our resources from, and how we relate to the wider society. These are all inherently political discussions, and to remove the politics from it leaves the movement open to this sort of co-optation.

Visions of the Future

There are multiple visions of the future when it comes to permaculture. Leahy examines three, the first of which is what he calls the town and village bio-regional vision. In this vision the ethics of permaculture would inform an economic system made up of ethical businesses and non-monetary community provisions, with large corporations replaced by small cooperatives. The gifting economy would prevail, with many people contributing to the overall system through a system of giving and receiving of resources without direct monetary exchanges. These “compacts” between industries and consumers to produce would substitute for money. Most of the economy would be supervised at the local level. In this vision local meaning a bio-regional definition of local, where borders are defined by water catchment basins, mountains, rivers, and other natural borders.

The first of what is called “degrowth visions” is the eco-modernist vision, the luxury gay space communism of the ecological movement, with new tech allowing sustainable growth and wealth accumulation. Finite resources are either reused or replaced with renewables. Digital technology necessitates cooperative and egalitarian organization, with this being referred to as ‘Post-capitalism’. This is similar to earlier theories that allowed for unlimited capitalism as new technology made for sustainable industrial growth.

In the second degrowth vision, none of this impossible. With the effect being de-industrialization and usually, population reductions. This view shares many worrying traits with the eco-fascist mindset of overpopulation. The degrowth visions would allow for a slow-paced lifestyle, as people live simpler lives, closer to home. There would be more community participation and workplace ownership, giving people more control over their daily lives.

Leahy delineates three views on how such a society might work, which he found prevalent among the permaculturists he spoke to:

- Radical reformism

- Eco-socialism

- The gift economy and the commons

Unfortunately, radical reformism seems to be dominant in the movement at the moment. The idea is to use the State to regulate carbon emissions and resource use within our natural limits. Proponents of this view suggest distributive measures to deal with the economic impact of the degrowth necessary to achieve output within reasonable limits.

A typical set of suggestions can be drawn from Degrowth in the Suburbs, a book by Samuel Alexander and Brendan Gleeson with a foreword by David Holmgren:

“Dropping GDP in favor of a genuine progress index, rolling back the privatization of government services, reducing resource use through caps, tradable energy quotas, working hour reductions, public spending on renewables, pricing carbon, tighter government control of the money supply, a debt jubilee, rights to housing security, population policy, the Universal Basic Income, a job guarantee, wealth taxes, aid for developing countries, government support for workers’ cooperatives.

This so-called “radical” reformism is no more likely to succeed in stopping the negative effects of capitalism and the State than any other reformist movement, as it seeks to maintain and strengthen the State, not abolish it. Any system of reform ultimately serves this strengthening and re-legitimizing role for the State. People flock to reform as a stop gap to actually doing the radical thing which is getting to the root of the problem. These two words have almost opposite meanings. To reform is no ignore the underlying systemic issues.

Eco-socialism authors agree that we have exceeded planetary bounds and need immediate degrowth. They propose that the means of production be taken from the capitalist class. A much more radical position than the reformists who claim the term. Yet the eco-socialist are still Statists in the end. They offer a “democratically” elected government that plans the economy with an eye to ecological damage prevention. They say that while there is room for some small businesses and worker owned cooperatives, most of the industry should be nationalized. An unfortunate backslide from taking the means of production only to hand them over to a centralized State.

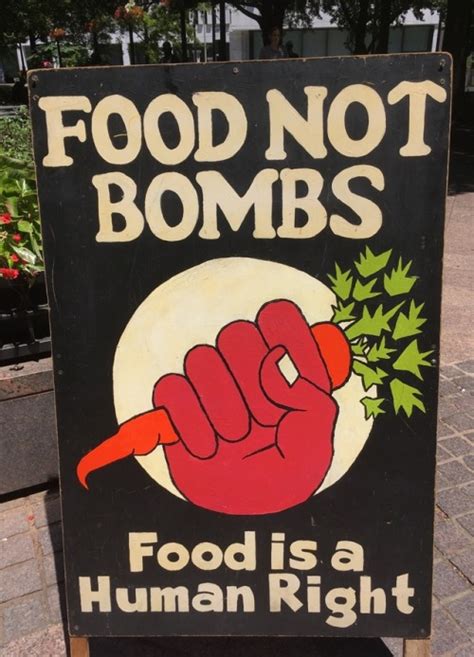

In the final vision we finally get to some ideas that resonate with an anarchist. The gift economy vision is a familiar concept to anyone who has heard of Food Not Bombs or been apart of a mutual aid collective. In this vision small local worker owned collective run the entire economic structure. The planet’s resources are shared in common with all according to need, work is given freely by ability and desire. Shared tools are used by people who make stuff for the community. Consumer’s needs are met by voluntary associations of worker’s who consult with the interested consumers to come to an arrangement to make and supply the goods or services. This vision completely does away with the need for money of any kind, no national authority is needed. This is a stateless and classless society that orders itself based on fulfilling it’s own needs within the boundary set by the planet.

In the final vision we finally get to some ideas that resonate with an anarchist. The gift economy vision is a familiar concept to anyone who has heard of Food Not Bombs or been apart of a mutual aid collective. In this vision small local worker owned collective run the entire economic structure. The planet’s resources are shared in common with all according to need, work is given freely by ability and desire. Shared tools are used by people who make stuff for the community. Consumer’s needs are met by voluntary associations of worker’s who consult with the interested consumers to come to an arrangement to make and supply the goods or services. This vision completely does away with the need for money of any kind, no national authority is needed. This is a stateless and classless society that orders itself based on fulfilling it’s own needs within the boundary set by the planet.

Co-founder Bill Mollison never wanted to dissuade people from the goals of the left or the environmental movements. Even he criticized the reformist vision of working with the State to achieve sustainability. He argued for a more self sufficient approach of grassroots community agricultural projects at a local level, a tactic linked with anarchist politics of direct action. ‘Small-scale experiments in the construction of alternative modes of social, political and economic organization’ enable us to avoid the dual pitfalls of ‘waiting forever for the Revolution to come’ or ‘perpetuating existing structures through reformist demands’, he said.

Conclusion

So we can see that something new is needed for permaculture to survive. The problematic roots and the current influx of far right ideas into ecological spaces mean that we are experiencing a crisis in permaculture at the moment. What is needed is to rethink the very core of permaculture’s apolitical history. We need to acknowledge the inherent politics in everything we do, in all the relationships we form with people and things. All the decisions we make throughout our day.

If permaculture is to continue it needs to be flexible enough to adapt to the changing political circumstances, it can no longer remain neutral. We have seen over the last few years that neutrality in the face of oppression is oppression. We risk siding with the far right by default if we do not take a stance of our own. They will move into our spaces and co-opt them, using our ecological language to code their white supremacist beliefs. Most anarchists are aware and on guard for this in normal life, but perhaps the average homesteader is not. This is a problem that needs to be remedied, and anarchists once again have a possible solution.

We will call it Anaculture, a new proposal for how to move forward. We will combine the lessons in anti authoritarian, horizontal, community organizing that anarchist understand with the ethical design system of permaculture. By working hand in hand we can create something that will allow us to keep what is good in permaculture while transforming it into something that includes everyone and is resistant to the incursion of far right ideologies.

In the following several articles I will expand and define this term and lay out the principles that anarchists have been developing for decades. This system should not be used as a rigid cononical text, but a jumping off point to think about what methods work best in our own community. We do not want a cookie cutter approach to community organizing. Let’s develop this project together, in conversation with each other, everyone adding in their own thoughts. Reach out if this speaks to you and let me know what you think. I can be reached at sabot_media@riseup.net.