Are humans inherently good or bad, and why should we, as Anarchists, care?

by Fox

Do we as radicals care about theological questions such as good and evil? Heaven and Hell? If not, then what sort of morality guides our political ambitions?

If humans are not inherently good then what does that mean for Anarchy?

Is it the supposition of Anarchism that we all are good people, just wanting throw off the chains of our oppressors to become the cooperative and loving people we all know we are? Some of these questions may be subjective, and to those we will leave it up to the reader to discern. But these question pose a huge challenge to all political activists. Not only must we be aware of these beliefs so that we can recognize them when we encounter them in others we are trying to organize with, but to better understand what our own beliefs are and where they come from.

I want to draw some distinctions and define some terms for this article. Here I will use religion to refer generally to the major organized and institutional religions of the world. This is separate from the concept of spirituality, as I take to be the feeling of connectedness with nature or some higher power, as felt by the individual. I do not wish to critique spirituality in general but to focus the discussion on Western Christianity specifically, with some generalizations of this type of religion insofar as those religions share certain characteristics that predispose them to authoritarianism.

It may be uncommon for most anarchists and leftist radicals to think about religion as a significant factor in organizing but it pervades all of our lives nonetheless. It will be the working theory of this article that the modern political divide is not, in fact, truly a divide between left and right ends of the political spectrum, but one of a more theological nature, going right back to the supposed very beginning of it all, Adam and Eve.

That is to say that the dichotomy of authoritarian vs anti authoritarian politics can also be examined through the lens of Original Sin. With this lens we can see the belief that people are good or evil as an indicator of a person’s political beliefs on whether people need rulers and laws to keep them in line or not. If a person believes this myth of original sin, whether or not they ascribe religious motivations to this belief, they are far more likely to want to control this evil behavior through the passing of laws, and the punishment of the transgressors of those laws. On the other hand, if one is inclined to believe that people are naturally good, then what you would seek is the removal of those controls that keep us all fighting and competing for resources.

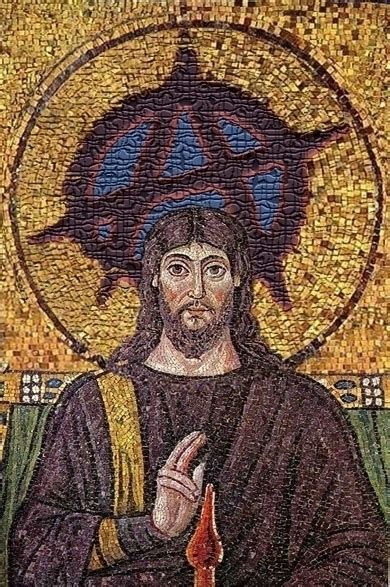

The Religion

Original sin is the Christian theocratic doctrine that supposes that all humans are inherently sinful and evil by birthright. The basis for the belief stems from the book of Genesis, and the story of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, as well as a handful of other passages throughout the Bible. Coming to prominence in the 3rd century, this belief was adopted into the official lexicon of the Church by the Councils of Carthage and Orange after the author Augustine of Hippo (345-430 CE) first used the phrase in his writings. Later protestant reformers such as Luther and Calvin would argue that this original sin lasted for life, even after baptism, preventing the person from ever doing good. This was a complete loss of human free will, except that of the will to sin.

Instead, the Catholic church says that

“Baptism, by imparting the life of Christ’s grace, erases original sin and turns a man back towards God, but the consequences for nature, weakened and inclined to evil, persist in man and summon him to spiritual battle”, and that “weakened and diminished by Adam’s fall, free will is yet not destroyed in the race.”

Judaism, on the other hand, doesn’t see human nature as irrevocably tainted by this original sin, and even the Christian church had no theocratic doctrine on the matter until the 4th century. It developed incrementally as early church fathers were inspired by the composition of The New Testament. Many earlier authors, though, assumed that children were born without sin.

As for the Bible itself, Genesis 3, the story of the Garden of Eden makes no association between sex and the disobedience of Adam and Eve, nor is the serpent associated with Satan, nor are the words “sin,” “transgression,” “rebellion,” or “guilt” mentioned; the words of Psalm 51:5 read: “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin my mother conceived me”, but while the speaker traces their sinfulness to the moment of their conception, there is little to support the idea that it was meant to be applicable to all humanity. While Paul in Romans writes that “through one man (i.e., Adam) sin entered into the world,” his meaning is not that God punishes later generations for the deeds of Adam, but that Adam’s story is representative for all humanity.

So we can see that even among religious scholars and authors there has been some debate about this matter for quite some time. The matter is more or less settled today though with most Christians believing in the inherently flawed nature of humanity to some degree. But this is merely where our story starts, the impetus for the cultural impact we see in our modern political landscape today. While many people outside the faith may not believe in the Bible or the idea of original sin if they were asked about it, they might, at the same time readily admit that they believe all people are inherently bad. Where else does this idea originate if not for the religious concept of original sin?

The impulse to authority is one side effect of this belief. Since, if you believe that everyone is bad by nature, then you clearly need some law and order to keep people in line. Otherwise it would be complete bedlam, or, as they say sometimes, anarchy. But if this is just a question debated by intellectual theocratic scholars why is it so pervasive in our society? Why, when religion in this country has been on a steady decline for years, must we continue to fight over this concept? It is not as easy to put to bed as the rest, perhaps. Perhaps this idea is more fundamental than religion, but religion is simply the framework it has manifested in.

Anarchists should resist this tendency to see all humans as evil, or good.

This dichotomy is useless for us in examining what is useful or not in human behavior. People are obviously neither all good or all bad, this is a flattening of a very nuanced discussion we need to be having.

The History

Throughout history, authoritarian leaders have adopted different policies towards religion, ranging from the state atheism of many communist countries to the drawing of support from religious leaders only to co-opt their power. Religion often serves to mediate conflict between the state and its citizens as well as defining the social hierarchy people fit into. Although some authoritarian leaders use religion to their advantage, some view it with suspicion, worrying that it may lead to rebellion, as it sometimes has. In Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church enjoys a state monopoly and state subsidies, as well as a blasphemy law that protects it from criticism. Unregistered or minority religions have been suppressed by state authoritarian regimes, such as house churches in China. In 1999, Falun Gong practitioners launched widespread protests against the Chinese government, which led to the persecution of Falun Gong.

Humans are profoundly moral animals. We live in social structures that demand a level of knowledge about, and empathy for, your fellow person. We could never have achieved this level of development without having some sense of a natural morality. These tendencies were examined by Peter Kropotkin in his seminal work, Mutual Aid, where he states that:

“The mutual-aid tendency in man has so remote an origin, and is so deeply interwoven with all the past evolution of the human race, that it has been maintained by mankind up to the present time, notwithstanding all vicissitudes of history.”

He continues saying that after humans passed through what he unfortunately calls the “savage [sic]” tribal phase of development, then the village community stage, finally humans began to develop a new type of social organization. This looked like a federation of villages grouped together into a city. The results of this new development was great for the sharing of resources and the effective cooperation of large numbers of people, but by the end of the fifteenth century these republics were originally corrupted by Roman Caesarism and after centuries finally fell to the growing military States of the time.

However, there was one last push by the masses of people, the peasants of medieval Europe, to reconstruct society on the old basis of mutual aid and support. Kropotkin claims that the new reforms of the Church were not merely a revolt against Catholic abuses, but also held up the ideals of free, and brotherly communities. Writings and sermons of this period point to the ideas of economic and social unity and mutual support of all humanity. Texts were circulated among the peasants and artists claiming that it was up to them to interpret the Bible according to their own understanding, and also included calls to return communal lands to the village community, and the abolition of feudalism. The true faith for these writers often being the faith of brotherhood, according to Kropotkin.

From Mutual Aid, “At the same time scores of thousands of men and women joined the communist fraternities of Moravia, giving them all their fortune and living in numerous and prosperous settlements constructed upon the principles of communism. Only wholesale massacres by the thousand could put a stop to this widely-spread popular movement, and it was by the sword, the fire, and the rack that the young States secured their first and decisive victory over the masses of the people.” Over the next three hundred year the growing number of States systematically weeded out all institutions that expressed the ideas of mutual aid and care of all.

Perhaps this is where humanity really became cursed, the point at which we sold our future for immediate earthly gains. When once we had a village community that served to meet the needs of the entire social order, increasingly people became part of a social hierarchy that saw more and more resources concentrated at the top and fewer and fewer avenues of legitimate recourse outside the corrupt processes of the State. This is when humans truly started acting in what some might describe as evil.

This newer form of social order has been a cancer on our moral sense ever since, corrupting and perverting it to the point where so many of us believe in the inherent flawed nature of humanity. It is likely the disaffection and isolation we all experience in our modern society that leads to this despondent worldview. A trend that began when city’s started to become empires. When humans started to forget their true nature, the good within us that still remains buried under the trappings of capitalism and consumerism.

The Science

Most modern scientific analysis of religiosity, or the expression of religious faith, including church attendance and affiliation, are positively linked with what scientist call the authoritarian personality cluster. This cluster of traits include submission to authority, conventionality, and intolerance. This correlation gets stronger the more towards the fundamentalist side of the scale you get. Fundamentalism has been correlated with traits such as low openness to experience, high rigidity, and low cognitive complexity. In particular, authoritarianism “is positively associated with a religion that is conventional, unquestioned, and unreflective”, according to Wink et al.’s longitudinal study of an American cohort born in the 1920s.

Over the years there have been hundreds of scientific articles written on this correlation, with both psychologists and sociologists having studied this area in depth. Wink et al. found that this effect held for traditional church-centered religion but not for those that are seeking non-institutional spirituality. The latter mode of religion is “characterized by an openness to new experiences and by creativity and experimentation, characteristics that are antithetical to the conventionality that adheres in authoritarianism”. The views of modern psychology is clear that humans, being social creatures, are very interested in the happenings of our neighbors, and the reasons for their actions. We like knowing how good and bad are defined, so we know who to avoid and who to stick around. Evolution has instilled in us the innate ability to recognize good and bad traits in others. With good traits generally being actions that benefit others (mutual aid) and bad traits being selfish acts.

From Paul Zak at Psychology Today:

Because our biology causes us to avoid pain, we typically avoid such actions. Similarly, we enjoy pleasure and vicariously experience pleasure when we do something that brings happiness to others. This “fellow-feeling,” or what we would now call empathy, is what maintains us in the community of humans. This is a critical requirement for a social creature.

So the biological answer to this question of are humans good or evil is simple… that’s the wrong question to be asking. Instead, asking why human behaviors exist gets to much more insight on the matter. We seek out situations and people that will increase our chances of evolutionary continuance. We are neither good or bad, those concepts are ours and ours alone. Humans are complex, social creatures who do things for a multitude of reasons from one day to the next. Behaviors can change and adapt over the long term as well. Paul Zak notes that when we are in a state of safety and stability, a biological morality suits us as it sustains our place in the community, which helps us maintain the basic needs for survival. The exception being roughly 5% of the population that has no oxytocin response and are pathologically selfish. This is a concern for any future society built without rulers, but since today these people generally rise to the top of the legal and medical professions, we can see that this system only serves to glorify those traits, instead of mitigating them.

When asked, “what about the murderers, and psychos” a proper anarchist response could be, “well we could at least stop giving them badges and electing them to office”.

The Politics

As anarchists we must believe in the better nature of humanity; our politics demand it.

We cannot persuade anyone to join us in toppling empires if the anarchy that comes after is full of sinners, now free to assault and pillage without recourse. This is not at all the society we have envisioned. The world we see is one of mutual aid, cooperation, joy, and revolutionary love. How does this square with the idea that all people are evil? I argue it cannot, in fact we must wholly reject this notion and consciously push back against the idea in our communities.

The idea of original sin, whether or not it has a religious basis in the individual, is toxic to any anti-authoritarian political movement. It will always revert back to ideas of controlling the populace to the benefit of a few, for fear of the masses having so much freedom they exert their power to cause mischief and violence. This is not our nature and we cannot let it be seen as such. Let’s take a look at some examples of historical anarchists and their positions on the matter of institutional religion and Christianity. While the idea of original sin is not usually touched on in specific, the idea is so fundamental to modern Christian beliefs that it underlies most of the religious phenomenon we do see discussed. It is the motivating factor in many of today’s religious activities, such as the anti-abortion movement, the anti-feminist movement, and the anti-LGBTQ2IAX+ movement, among others.

In her essay, The Failure of Christianity early Jewish American anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman said,

“I am not interested in the theological Christ. Brilliant minds like Bauer, Strauss, Renan, Thomas Paine, and others refuted that myth long ago. I am even ready to admit that the theological Christ is not half so dangerous as the ethical and social Christ. In proportion as science takes the place of blind faith, theology loses its hold. But the ethical and poetical Christ-myth has so thoroughly saturated our lives that even some of the most advanced minds find it difficult to emancipate themselves from its yoke. They have rid themselves of the letter, but have retained the spirit; yet it is the spirit which is back of all the crimes and horrors committed by orthodox Christianity. The Fathers of the Church can well afford to preach the gospel of Christ. It contains nothing dangerous to the regime of authority and wealth; it stands for self-denial and self-abnegation, for penance and regret, and is absolutely inert in the face of every [in]dignity, every outrage imposed upon mankind. [sic]. Good and bad, punishment and reward, sin and penance, heaven and hell, as the moving spirit of the Christ-gospel have been the stumbling-block in the world’s work. It contains everything in the way of orders and commands, but entirely lacks the very things we need most.”

Despite the use of words to describe his studies that today might get him a good calling in, Peter Kropotkin saw so called “primitive [sic]” superstitions as the source of all morality, based on the sympathy and unity inherent in collective group life. With mutual aid as a central indicator of a successful and healthy social life, he saw the moral base of action to be akin to the golden rule of, do unto others as you would have others do unto you”. A simple way to keep good order within a socially healthy community.

Despite the use of words to describe his studies that today might get him a good calling in, Peter Kropotkin saw so called “primitive [sic]” superstitions as the source of all morality, based on the sympathy and unity inherent in collective group life. With mutual aid as a central indicator of a successful and healthy social life, he saw the moral base of action to be akin to the golden rule of, do unto others as you would have others do unto you”. A simple way to keep good order within a socially healthy community.

Kropotkin then says that this natural morality has been corrupted by law, religion and authority. Further that this new social order was set up and maintained by rulers, priests, and the wealthy for their own benefit, not for the common good. Therefore, modern concepts of morality are nothing more than the powerful ruling class’s instrument to protect their privileged way of life. He even defends the morality of killing for the benefit of mankind as a whole, such as the assassination of tyrants, but never for oneself.

He rejected the idea of punitive justice as an effective tool for controlling behavior, seeing love and hate as greater forces. His morality was not based in doing good deeds in order to get benefit for yourself, but instead on living a rich and joyous life and doing all you can for your fellow humans. Not in a spirit of charity, but in one of solidarity.

The historical tradition of Anarchism is ripe with examples of this anti-religious trend. From Nicolas Walter in his piece Anarchism and Religion:

Revolutionary anarchism, like revolutionary socialism, has quasi-religious features expressed in irrationalism, utopianism, millennialism, fanaticism, fundamentalism, sectarianism, and so on. But anarchism, like socialism and liberalism, also has anti-religious features all of them modern political ideologies tending to assume the rejection of all orthodox belief and authority and is the supreme example of dissent, disbelief, and disobedience. All progressive thought, culminating in humanism, depends on the assumption that every single human being has the right to think for himself or herself; and all progressive politics, culminating in anarchism, depends on the assumption that every single human being has the right to act for himself or herself.

There is no doubt that the prevailing strain within the anarchist tradition is opposition to Christianity. William Godwin, the author of the Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), the first systematic text of libertarian politics, was a Calvinist minister who began by rejecting Christianity, and passed through deism to atheism and then what was later called agnosticism. Max Stirner, the author of The Individual and His Property (1845), the most extreme text of libertarian politics, began as a left-Hegelian, post-Feuerbachian atheist, rejecting the ‘spooks’ of religion as well as of politics including the spook of ‘humanity’. Proudhon, the first person to call himself an anarchist, who was well known for saying, ‘Property is theft’, also said, ‘God is evil’ and ‘God is the eternal X’.

Bakunin, the main founder of the anarchist movement, attacked the Church as much as the State, and wrote an essay which his followers later published as God and the State (1882), in which he inverted Voltaire’s famous saying and proclaimed: ‘If God really existed, he would have to be abolished.’ Kropotkin, the best-known anarchist writer, was a child of the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution, and assumed that religion would be replaced by science and that the Church as well as the State would be abolished; he was particularly concerned with the development of a secular system of ethics which replaced supernatural theology with natural biology. Errico Malatesta and Carlo Cafiero, the main founders of the Italian anarchist movement, both came from freethinking families (and Cafiero was involved with the National Secular Society when he visited London during the 1870s).

Eliseé and Elie Reclus, the best-loved French anarchists, were the sons of a Calvinist minister, and began by rejecting religion before they moved on to anarchism. Sebastien Faure, the most active speaker and writer in the French movement for half a century, was intended for the Church and began by rejecting Catholicism and passing through anti-clericalism and socialism on the way to anarchism. Andre Lorulot, a leading French individualist before the First World War, was then a leading freethinker for half a century. Johann Most, the best-known German anarchist for a quarter of a century, who wrote ferocious pamphlets on the need for violence to destroy existing society, also wrote a ferocious pamphlet on the need to destroy supernatural religion called The God Plague (1883). Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker), the great Dutch writer, was a leading atheist as well as anarchist. Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, the best-known Dutch anarchist, was a Calvinist minister who began by rejecting religion before passing through socialism on the way to anarchism. Anton Constandse was a leading Dutch anarchist and freethinker.

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, the best-known Jewish American anarchists, began by rejecting Judaism and passing through populism on the way to anarchism. Rudolf Rocker, the German leader of the Jewish anarchists in Britain, was another child of the Enlightenment and spoke and wrote on secular as much as political subjects. In Spain, the largest anarchist movement in the world, which has often been described as a quasi-religious phenomenon, was in fact profoundly naturalistic and secularist and anti-Christian as well as anti-clerical. Francisco Ferrer, the well-known Spanish anarchist who was judicially murdered in 1909, was best known for founding the Modern School which tried to give secular education in a Catholic country.

The leaders of the anarchist movements in Latin America almost all began by rebelling against the Church before rebelling against the State. The founders of the anarchist movements in India and China all had to begin by discarding the traditional religions of their communities. In the United States, Voltairine de Cleyre was (as her name suggests) the child of freethinkers, and wrote and spoke on secular as much as political topics. The two best-known American anarchists today (both of Jewish origin) are Murray Bookchin, who calls himself an ecological humanist, and Noam Chomsky, who calls himself a scientific rationalist. Two leading figures of a younger generation, Fred Woodworth and Chaz Bufe, are militant atheists as well as anarchists.

It is because of this shying away or full rejection of religion that anarchists have missed this trend towards viewing humans as evil or bad. By not engaging with religious studies and critiques of religion, not only did we miss out on this crucial paradigm, but we essentially alienated a good portion of the population. Without an eye and an ear to religion at least we can’t expect to make headway is the long struggle to bring people to anarchy. We must know and care about the religious communities if we expect to dialogue with them and find any common ground to organize. Without this block of support our ideas may be doomed to be relegated to a sub-cultural phenomenon at best, and at worst might slip into the sort of anti-theism that rejects so many cultural practices around the world. The sense today is that modern anarchists are starting to find ways to practice a certain form of spirituality without sacrificing their morality or values. If we can find ways to reach common ground with other spiritual practices then we only stand to gain many comrades in our fight against authoritarianism.

Conclusion

So we can see that the trend towards anti-religious sentiments is strong within historical Anarchism. But anarchists are not without morality. Especially within the modern anarchist movement ideas of radical love, militant joy, mutual aid are very popular. These tenants are founded in the idea that humans are inherently good, that without the confines of the State we would again flourish as social creatures to take care of all those in our society.

To call this current system a moral one is a joke, the ideas of Anarchism are the direct result of years of thinkers ruminating on the morality of humankind, coming to the conclusion that humans are not born sinners, but born free. Free to choose what to do with their life, free to choose how to relate to their neighbors. It is with this base that the thoughts of Anarchy have moved forward into the new century, ready to tackle the old notions of original sin. But do we realize this is the terrain of the battlefield we fight on? Are we taking into account these religious undertones of our opponents views on humanity’s nature?

To do this we must examine this dichotomy and come up with strategies that counter this myth with facts. We cannot simply proclaim that there should be no rulers. To the person suffering under the belief that all humanity is naturally evil, this sounds like a terrible idea. We have to first dissuade people of this notion. Only then can we begin to convince people that what we want is not chaos incarnate but a society built on cooperation and love. Whether or not individuals realize it, their beliefs about humanity’s nature shape their view on authority. We cannot expect to effectively challenge one without challenging the other.

This could be a new site of struggle for radicals, seizing upon a novel terrain on which to debate our opponents and win over more people for anarchy. This is not a call to make anarchy a religion by any means, we have established the toxicity of that type of institutional hierarchical religiosity. What is needed is for us to see that our current struggle against authoritarianism is a hard battle to fight, and the more avenue for attack the better off we are. This issue is a excellent site to attack, this pervasive idea that we are tainted by birth, that all humans are inherently one way or another. We need to advance both a scientific critique and a religious one. As this and future texts will aim to do. The worst thing we can do is to cede this territory to our enemies and watch as they co-opt the religiously inclined to their own benefit.

We need to have solidarity with these faithful comrades who need help seeing that it is the trappings of this social order that make us act selfishly, we have nothing to loose but our chains.

Sources:

Boring, M. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664255923.

Toews, John (2013). The story of original sin. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781620323694.

Alter, Robert (2009). The Book of Psalms. W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393337044.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/emma-goldman-the-failure-of-christianity

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-anarchist-morality

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/nicolas-walter-anarchism-and-religion

Wills, Matthew (25 July 2017). “What Links Religion and Authoritarianism?”. JSTOR Daily.

Leak, Gary K.; Randall, Brandy A. (1995). “Clarification of the Link between Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Religiousness: The Role of Religious Maturity”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 34 (2): 245–252. doi:10.2307/1386769. ISSN 0021-8294.

Wink, Paul; Dillon, Michele; Prettyman, Adrienne (2007). “Religiousness, Spiritual Seeking, and Authoritarianism: Findings from a Longitudinal Study”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 46 (3): 321–335. ISSN 0021-8294.

Burge, Ryan P. (2018). “Authority, Authoritarianism, and Religion”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.667.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-mutual-aid-a-factor-of-evolution